R-Ratio Calculator for Antibiotic-Induced Liver Injury

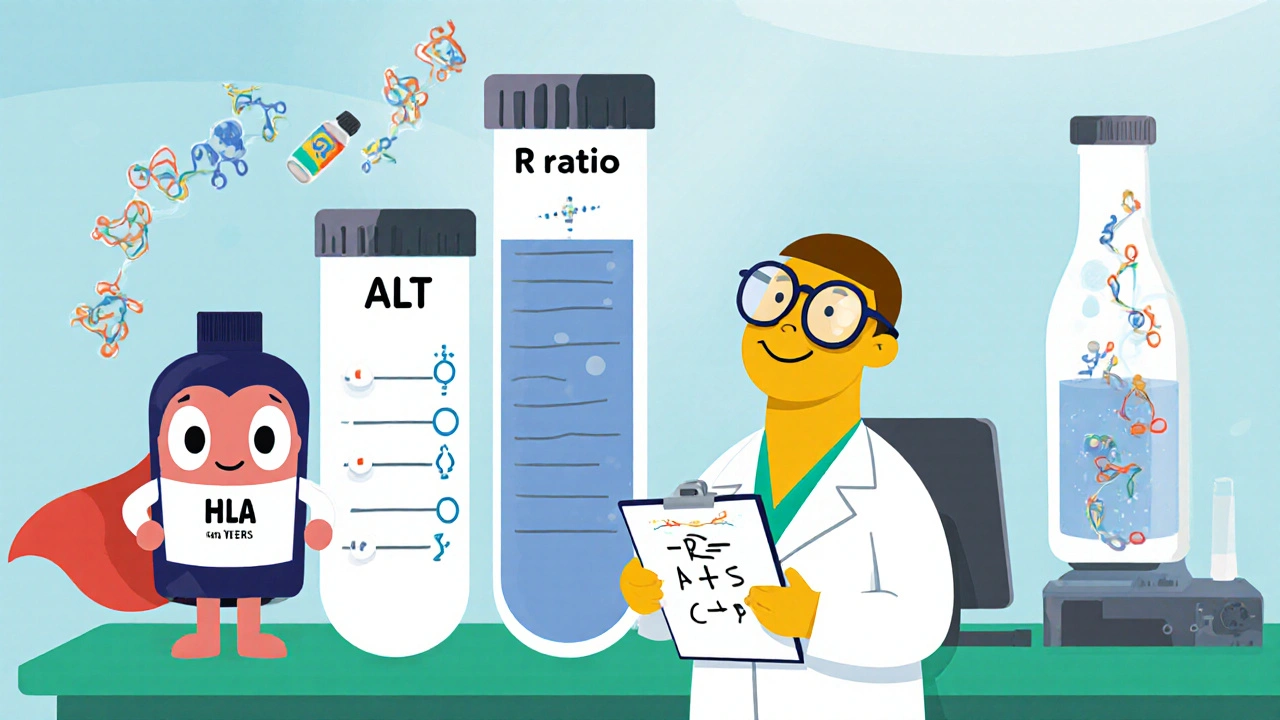

R-ratio = (peak ALT ÷ ALT ULN) ÷ (peak ALP ÷ ALP ULN)

Interpretation:

- >5 = Hepatocellular injury (hepatitis)

- <2 = Cholestatic injury

- 2-5 = Mixed or indeterminate pattern

Note: ULN values are typically 40 for ALT and 120 for ALP, but may vary by lab.

When a common infection meets a powerful drug, the liver can sometimes get caught in the crossfire. Antibiotic liver injury is a form of drug‑induced liver injury (DILI) that occurs specifically after taking antibiotics. It shows up as either hepatitis (damage to liver cells) or cholestasis (blocked bile flow), and the pattern depends on the drug, dose, and the patient’s own biology.

Why antibiotics can hurt the liver

Antibiotics aren’t meant to target liver cells, yet several mechanisms let them cause trouble:

- Mitochondrial dysfunction - many antibiotics interfere with the mitochondria’s ability to burn fatty acids, leading to energy failure and cell death.

- Formation of reactive metabolites that bind to proteins and trigger an immune‑mediated attack.

- Alteration of the gut microbiome, which weakens the intestinal barrier and allows bacterial products to reach the liver, worsening inflammation.

- Genetic susceptibility, especially certain HLA alleles, that makes a subset of patients especially prone to idiosyncratic reactions.

Two main injury patterns

Clinicians separate antibiotic‑related injury into three categories based on lab values using the R‑ratio:

- Hepatocellular (hepatitis) - ALT rises >5× the upper limit of normal (ULN); R‑ratio >5.

- Cholestatic - ALP rises >2× ULN; R‑ratio <2.

- Mixed injury - values sit in the middle (2 ≤ R ≤ 5) and both enzymes are elevated.

Understanding the pattern guides monitoring frequency and informs how urgently the offending antibiotic should be stopped.

Which antibiotics are most often blamed?

Not all antibiotics carry the same risk. The table below summarizes the three drugs that dominate DILI reports.

| Antibiotic | Typical injury pattern | Incidence (cases/100 000 prescriptions) | Time to onset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin‑clavulanate | Cholestatic (R < 2) | 15‑20 | 1‑6 weeks |

| Ciprofloxacin | Mixed (R ≈ 3) | 1‑3 | 1‑2 weeks |

| Piperacillin‑tazobactam (TZP) | Mixed/ hepatocellular | ≈28 % of ICU patients on ≥7 days therapy | Within 1‑2 weeks |

Amoxicillin‑clavulanate tops the list with a high‑risk ‘cholestatic’ signature, while fluoroquinolones and β‑lactam/β‑lactamase inhibitor combos often give a mixed picture.

Key risk factors beyond the drug itself

- Course length ≥7 days - risk rises over three‑fold (Shiraishi et al., 2024).

- Sepsis or severe infection - increases injury odds by ~1.8×.

- Male gender for certain agents (e.g., meropenem shows a 2.4× higher rate in men).

- Pre‑existing liver disease or alcohol use.

- Genetic markers such as HLA‑B*57:01 that predispose to idiosyncratic DILI.

How to catch it early

Monitoring protocols differ by risk category. A typical workflow looks like this:

- Obtain baseline ALT, AST, ALP, bilirubin, and INR before starting a high‑risk antibiotic.

- Repeat labs at 1‑2 weeks for amoxicillin‑clavulanate; for ICU patients on broad‑spectrum agents, check weekly.

- If ALT >5× ULN or ALP >2× ULN *and* the patient has symptoms (jaundice, fatigue, nausea), consider stopping the drug per AASLD guidelines.

- Calculate the R‑ratio to classify the pattern and guide further work‑up.

The “rule of 5” (ALT > 5× ULN or ALP > 2× ULN with symptoms) is widely used, though some centers tweak thresholds based on alternative treatment options.

Diagnostic steps beyond the labs

- Rule out viral hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis, and ischemic injury - especially in critically ill patients.

- Review medication list for other hepatotoxic agents.

- Imaging (ultrasound) can identify biliary obstruction that mimics cholestasis.

- In ambiguous cases, a liver biopsy may reveal drug‑related eosinophils and necrosis.

Treatment - stop, support, and substitute

There’s no antidote for most antibiotics. Management focuses on three pillars:

- Discontinue the offending antibiotic as soon as the injury pattern is recognized.

- Start an alternative agent that covers the infection but has a lower hepatotoxic profile (e.g., switch from amoxicillin‑clavulanate to a narrow‑spectrum penicillin when feasible).

- Provide hepatoprotective support - N‑acetylcysteine has been studied in non‑acetaminophen DILI with modest benefit; the evidence for routine use is still evolving.

Most patients improve within weeks once the drug is stopped, but severe cases may need hospital admission for monitoring of coagulopathy and encephalopathy.

Emerging strategies and future outlook

Research is moving from reactive to predictive:

- Microbiome profiling - low Faecalibacterium prausnitzii levels have been linked to a 3.7‑fold higher DILI risk, paving the way for pre‑treatment screening.

- Pharmacogenomics - HLA testing could identify patients at risk for certain β‑lactams, potentially cutting incidence by up to 40 % within the next decade.

- Probiotic adjuncts - ongoing Phase 2 trials (NCT05217834, NCT04987215) assess whether restoring gut diversity reduces cholestatic injury from broad‑spectrum agents.

- Real‑time liver‑function monitoring devices are in development, aiming to give clinicians bedside alerts when ALT or ALP spikes.

Regulators are also tightening post‑marketing surveillance. The FDA now requires any new antibiotic to submit a hepatotoxicity risk assessment within 6 months of approval, and the EMA’s 2023 update added specific monitoring recommendations for β‑lactam/β‑lactamase inhibitor combos.

Quick Takeaways

- Antibiotic liver injury accounts for ~64 % of all DILI cases.

- Amoxicillin‑clavulanate is the highest‑risk single agent, mainly causing cholestasis.

- Use the R‑ratio to differentiate hepatitis from cholestasis.

- Course length ≥7 days, sepsis, and certain HLA types dramatically raise risk.

- Baseline labs + early repeat testing catch injury before it becomes severe.

What is the R‑ratio and how is it calculated?

R‑ratio = (peak ALT ÷ ALT ULN) ÷ (peak ALP ÷ ALP ULN). Values >5 signal hepatocellular injury, <2 signal cholestasis, and 2‑5 indicate a mixed pattern.

Which antibiotics should I monitor most closely?

Amoxicillin‑clavulanate, piperacillin‑tazobactam, and fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin) have the highest reported rates of DILI. For high‑risk patients, check liver enzymes at week 1 and weekly thereafter if therapy extends beyond 7 days.

Can probiotics prevent antibiotic‑related liver injury?

Early trial data suggest probiotics may blunt gut dysbiosis and lower cholestatic risk, but definitive evidence is still pending. Clinicians can consider them on a case‑by‑case basis while awaiting trial results.

What should I do if a patient develops jaundice on a β‑lactam?

Stop the β‑lactam immediately, obtain a full liver panel, and start an alternative antibiotic without known hepatotoxicity. Monitor INR and bilirubin daily; consult hepatology if values rise rapidly or encephalopathy appears.

Is there a role for genetic testing before prescribing antibiotics?

HLA screening is not yet routine, but in patients with a history of DILI or strong family history, testing for alleles like HLA‑B*57:01 can guide safer antibiotic choices.

11 Comments

naoki doe

Interesting rundown, but it feels like the article skimmed over the real-world nuances of switching antibiotics-especially when patients are already on multiple meds. It’s not just about the R‑ratio; drug‑drug interactions can flip the script entirely.

Joy Dua

While the overview enumerates mechanisms, it omits the glaring fact that hepatotoxicity risk is dose‑dependent and that the metabolic idiosyncrasy of each patient can render standard thresholds moot.

Barna Buxbaum

Great summary! 😊 If you’re monitoring a patient on amoxicillin‑clavulanate, keep an eye on ALP early – you’ll catch cholestasis before it turns into a full‑blown issue.

Abbey Travis

Just a heads‑up for anyone prescribing: a quick baseline LFT panel before starting a 7‑day course can save a lot of trouble down the line.

ahmed ali

Alright, let me lay it all out because the “quick takeaways” are far from quick when you dig into the literature. First, the claim that antibiotics account for roughly 64 % of DILI is based on older cohort studies that didn’t factor in newer broad‑spectrum agents, so the actual figure might be shifting. Second, you mention mitochondrial dysfunction as a universal mechanism, yet recent in‑vitro data suggest that only a subset of β‑lactams cause significant oxidative stress, namely those with bulky side chains. Third, the R‑ratio is useful, but clinicians often overlook that ALT and ALP can be transiently elevated for reasons unrelated to hepatotoxicity, such as muscle injury or bone turnover, respectively. Fourth, genetics – the HLA‑B*57:01 allele is linked to flucloxacillin injury, but the odds ratio varies dramatically across ethnicities; a blanket recommendation for HLA screening isn’t cost‑effective yet. Fifth, the gut microbiome angle is fascinating, but the correlation with Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is still correlative, not causative – we need mechanistic studies before using it as a screening tool. Sixth, the article glosses over the role of drug metabolism pathways like CYP3A4 inhibition, which can raise plasma levels of co‑administered agents and indirectly worsen liver injury. Seventh, you suggest N‑acetylcysteine has modest benefit, but a meta‑analysis from 2022 actually showed a statistically significant reduction in mortality for non‑acetaminophen DILI when administered within 48 hours. Eighth, the “rule of 5” is a handy heuristic, but it fails in cases where patients have chronic liver disease and baseline enzymes are already elevated. Ninth, imaging isn’t just about ruling out obstruction; elastography can differentiate between acute injury and underlying fibrosis, guiding management. Tenth, biopsies may reveal eosinophils, but they’re not routine and carry bleeding risk, so reserve them for refractory cases. Eleventh, proactive stewardship programs that limit unnecessary broad‑spectrum antibiotics have shown a 30 % drop in DILI incidence in hospitals that implemented them. Twelfth, real‑time liver monitoring devices are promising, but they’re still experimental and not widely available. Thirteenth, regulatory changes are good on paper, but compliance varies, especially in lower‑resource settings where post‑marketing surveillance is weak. Fourteenth, you didn’t mention that prolonged cholestasis can lead to fat‑soluble vitamin deficiencies, which requires supplementation. Fifteenth, clinicians should always consider alternative agents like doxycycline for certain infections when the patient has a known HLA risk. Finally, keep in mind that the landscape is evolving – what’s low‑risk today might not be tomorrow as new data emerge.

Deanna Williamson

The pharmacogenomic aspects are indeed promising, yet without standardized testing protocols, their clinical utility remains limited.

Miracle Zona Ikhlas

Stay vigilant with baseline labs.

Samantha Taylor

Oh sure, because we all have time to order a full genetic panel before prescribing a simple course of antibiotics – reality check, folks.

Joe Langner

Very insightful! Remember, the liver has an incredible regenerative capacity, so early detection usually leads to full recovery.

Ben Dover

While the long‑winded exposition offers depth, it overlooks the practical bedside decision‑making algorithms that most clinicians rely upon, thereby limiting its immediate applicability.

Katherine Brown

I appreciate the thoroughness, however, a more concise synthesis could enhance accessibility for a broader audience.