Most people assume that when a pill hits its expiration date, it’s useless-or worse, dangerous. You’ve probably tossed out old antibiotics, painkillers, or allergy meds the moment the date passed. But what if those pills were still perfectly safe and effective years later? The Military Shelf Life Extension Program (SLEP) proves that’s not just possible-it’s happening right now, on a massive scale.

How the Military Keeps Medicines Working for Decades

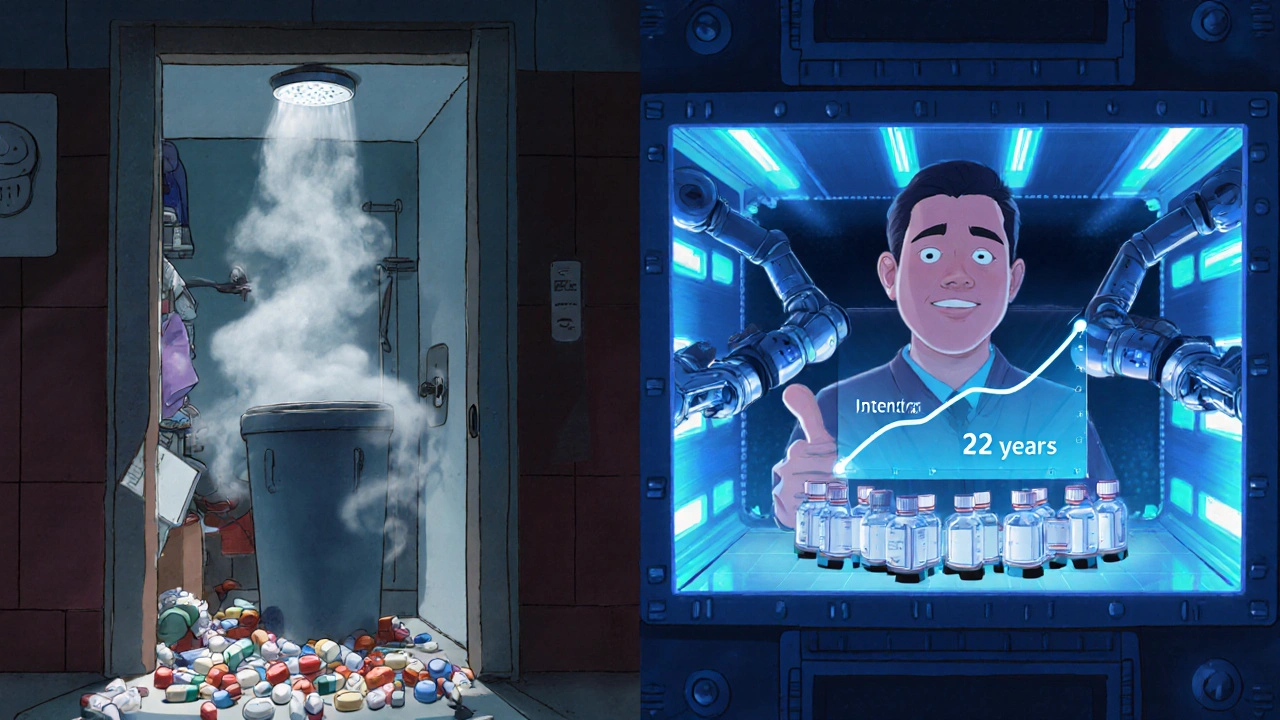

In 1986, the U.S. Department of Defense started asking a simple question: What if drugs didn’t really expire when the label said they did? At the time, federal stockpiles of critical medicines-like anthrax antitoxins, nerve agent antidotes, and antibiotics for battlefield use-were being destroyed simply because they’d passed their printed expiration dates. The cost was staggering. So they began testing them. The results shocked even experts. A 2006 study by the FDA found that 88% of 122 tested drugs still met potency standards more than 15 years past their labeled expiration. Some stayed above 90% effective for over two decades. That’s not a fluke. Since then, SLEP has extended the shelf life of more than 2,500 different drug products. The program doesn’t guess. It tests. Every lot, every time. SLEP follows strict rules. Drugs are stored in climate-controlled warehouses-constant temperature, low humidity, sealed packaging. Samples are pulled every 1 to 3 years and sent to FDA labs. To qualify for an extension, the drug must retain at least 85% of its original potency. If it passes? The expiration date gets pushed back. Often by two or three years. Some drugs have been extended multiple times. One batch of doxycycline, for example, was cleared for use 22 years after manufacture.Why Commercial Drugs Don’t Get This Treatment

You won’t see this in your local pharmacy. Why? Because the pharmaceutical industry sets expiration dates based on short-term stability tests-usually 2 to 3 years. These aren’t designed to find how long a drug can last. They’re designed to cover manufacturers’ legal liability. If a drug fails after 3 years, the company isn’t responsible. So they don’t test beyond that. The military doesn’t have that luxury. They can’t afford to replace $8.5 billion worth of stockpiled drugs every few years. So they test for real-world durability. And the data they’ve collected is overwhelming: under proper storage, most solid-dose medications-tablets, capsules, powders-remain stable far longer than labels suggest. The FDA itself admits this. In 2019, Dr. Lawrence Yu, a former deputy director at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said: “The data from SLEP has fundamentally changed our understanding of drug stability in properly stored conditions.” He added that expiration dates are often more conservative than necessary.The Real Cost of Throwing Away Expired Drugs

Every year, Americans throw away roughly $1.7 billion worth of expired medications. Hospitals, pharmacies, and households discard pills, syringes, and vials that are still good. The military doesn’t do that. Between 2005 and 2015, SLEP saved the federal government an estimated $2.1 billion by avoiding unnecessary replacements. In 2020 alone, the Strategic National Stockpile extended the shelf life of Tamiflu by three years, preserving 22 million treatment courses. That’s not just money saved-it’s lives protected. If a pandemic hits, you don’t want to be told, “Sorry, our stock expired last year.” Military medical facilities that follow SLEP protocols cut pharmaceutical waste by 38%. That’s $87 million saved annually. And it’s not just about cost. It’s about readiness. In a crisis, you need medicine now-not in six months when new shipments arrive.

What SLEP Doesn’t Tell You

But here’s the catch: SLEP doesn’t apply to your medicine cabinet. The program only extends expiration dates for specific lots, stored under strict conditions-controlled temperature, sealed containers, no exposure to light or moisture. If you keep your ibuprofen in a bathroom cabinet where humidity swings from 20% to 90%, don’t assume it’s still good after five years. SLEP’s findings are not a green light for hoarding expired drugs at home. Dr. Michael D. Swartzburg, a pharmaceutical stability expert at UCSF, warns: “SLEP’s findings shouldn’t be generalized to all drugs or all storage conditions.” The program tests only FDA-approved prescription drugs-not over-the-counter meds, not liquids, not insulin, not biologics (though those are now being added slowly since 2021). The FDA is very clear: shelf-life extensions under SLEP are lot-specific. Just because one batch of metformin lasted 18 years doesn’t mean yours will. The packaging, storage, and manufacturing conditions matter. And if a drug is exposed to heat, moisture, or sunlight? All bets are off.How SLEP Is Changing the World

SLEP didn’t just save money-it changed global thinking. Since 2010, 12 NATO allies have built their own shelf-life extension programs modeled after the U.S. system. Countries like Canada, Germany, and Australia now test their stockpiled drugs instead of automatically discarding them. Even the World Health Organization has taken notice. In 2022, WHO published guidelines recommending that countries with limited resources consider stability testing before destroying stockpiled medicines during public health emergencies. And it’s not just about military use. The program’s data is helping scientists design better packaging, improve storage standards, and even rethink how expiration dates are calculated. The FDA’s 2022-2026 Strategic Plan includes expanding predictive modeling using advanced tools like mass spectrometry to forecast drug degradation more accurately.

What You Can Learn from SLEP

You’re not in the military. You don’t have access to FDA labs. But you can still use SLEP’s lessons to make smarter choices.- Store medications in a cool, dry place-not the bathroom or near the stove.

- Keep pills in their original containers with desiccants intact.

- Don’t assume expired drugs are dangerous. Most solid medications lose potency slowly, not suddenly.

- Check with your pharmacist before tossing out anything. Some drugs, like epinephrine or insulin, are time-sensitive. Others, like aspirin or acetaminophen, may still be effective years later.

What’s Next for SLEP?

The program is growing. In 2023, Congress approved funding to expand SLEP to cover more chemical, biological, and nuclear countermeasures. A new electronic system launched in late 2022 cut extension decision times from 14 months to under 8 months. The goal? To make the system faster, more reliable, and more scalable. But challenges remain. Funding is tight. A 2023 Congressional Budget Office report estimated that full expansion would require an extra $75 million per year. And as new drugs-especially complex biologics-are added to stockpiles, scientists are still learning how they degrade over time. Still, the evidence is clear: drugs don’t just die on a calendar. They fade slowly, if at all, when treated right. The military didn’t invent this truth. They proved it.Are expired medications dangerous to take?

For most solid medications-like tablets and capsules-expired drugs are rarely dangerous. They usually just lose potency over time. The FDA and CDC state that very few drugs become toxic after expiration. The main risk is reduced effectiveness, which could mean treatment fails. Liquid medications, insulin, and antibiotics like tetracycline are exceptions and should be discarded at expiration.

Can I extend the shelf life of my home medicine like the military does?

No. The Military Shelf Life Extension Program requires lab testing under controlled conditions that aren’t available to the public. You can’t replicate SLEP at home. But you can store your meds properly: in a cool, dry place, away from sunlight and moisture, and in original packaging. That helps them last longer naturally.

How does the military decide which drugs to test?

The Department of Defense prioritizes drugs that are critical for national defense and public health emergencies-like antibiotics, antivirals, antidotes, and vaccines. Drugs with a history of stability are tested first. The SLEP database tracks which lots have been tested and extended, and only those with documented storage compliance are eligible.

Do all drugs respond the same way to long-term storage?

No. Solid dosage forms like tablets and capsules are the most stable. Liquids, creams, and injectables degrade faster. Biologics-like vaccines and monoclonal antibodies-are especially sensitive to temperature and light. SLEP tests each drug type separately. A 20-year-old aspirin tablet might still work; a 20-year-old insulin vial would not.

Why hasn’t the FDA changed expiration date rules for all drugs?

Changing labeling rules would require massive regulatory overhaul. The FDA currently requires manufacturers to prove stability only up to the labeled date. Extending that would mean longer, costlier testing for every drug-which the industry resists. SLEP works because it’s a government program with public funding. Private companies don’t have the same incentives to test beyond 2-3 years.

13 Comments

Rekha Tiwari

Wow, I never thought about this! I’ve been tossing my old ibuprofen like it’s radioactive 🤯 But now I’m wondering if my bathroom cabinet is actually killing my meds instead of the date on the bottle. Gonna move mine to a drawer tonight.

Leah Beazy

This is wild. I work in a pharmacy and we throw out so much expired stuff daily. I had no idea the military was doing this. Makes me feel kinda guilty lol. Also, why are we paying for all this waste when the science says it’s fine? 🤔

John Villamayor

I read this and immediately thought about my grandpa who kept his blood pressure pills in a tin box in his sock drawer for 10 years and still took them like nothing happened. He’s 92 and still mows his lawn. Maybe he was onto something

Jenna Hobbs

OMG I’m crying. Not because I’m sad, but because this is one of those moments where science finally catches up to what people have been doing for decades. My grandma stored all her meds in the fridge, kept them in original bottles, and never threw anything out until it turned to dust. She’s 89. I’m starting to think she was a genius. 🙌

Ophelia Q

Just saved this for my mom. She’s always panicking about expired meds. This will make her feel way better. Also, side note: if you’re storing aspirin in a humid bathroom, you’re basically making a science experiment. Don’t do it. 😅

Elliott Jackson

Let me get this straight - the government spent billions testing pills so we don’t have to throw them away… but your local CVS still throws out $200 worth of Tylenol every week because the date says so? This isn’t science. This is corporate theater. 🤡

McKayla Carda

Storage matters more than the date. Cool, dry, dark. That’s it. No magic expiration fairy.

Christopher Ramsbottom-Isherwood

So you’re telling me the entire pharmaceutical industry is lying to us? Or just… incompetent? Because if 88% of drugs still work after 15 years, then why are we being sold this fear-based marketing? This feels like a scam. I’m not buying pills anymore unless they come with a lab report.

Stacy Reed

Think about it deeper though - if drugs don’t expire, then what does that say about time itself? Are we just afraid of decay? Are expiration dates a metaphor for our own mortality? We label things to control the uncontrollable. The pill doesn’t die. We just can’t handle the uncertainty.

Robert Gallagher

I’ve been storing my meds in a sealed plastic container in the basement since 2018. No heat, no light, no moisture. My doxycycline is from 2019. Still looks fine. I’m not taking it unless I’m in a zombie apocalypse, but if I am? I’m not wasting it. SLEP is the real MVP.

Howard Lee

The FDA’s position on expiration dates is technically accurate but practically misleading. Manufacturers are required to demonstrate stability only up to the labeled date. Beyond that, no data is required - which creates a vacuum filled by fear, not science. SLEP fills that vacuum with evidence.

Nicole Carpentier

Just told my roommate to stop tossing my old allergy pills. She looked at me like I was crazy. Now I’m gonna send her this article. Maybe she’ll stop acting like expiration dates are the law of the universe. Also - who’s with me on making a #DontTossYourPills hashtag? 🙋♀️

Hadrian D'Souza

Oh wow, so the military found out drugs don’t magically turn into poison after 3 years? Shocking. Next they’ll tell us water doesn’t expire either. Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry is out here selling you a new bottle of Advil every 18 months because your grandma’s 2017 stash might’ve lost 0.3% potency. We’re not living in a world of science - we’re living in a world of profit margins and liability waivers. And you? You’re the cash register.