Hypokalemia Management Calculator

Potassium Replacement

Enter potassium level to see recommendation...

Critical Considerations

Recommendations will appear here based on your inputs...

Additional Recommendations

Recommendations will appear here...

Next Steps

Follow-up monitoring schedule will appear here...

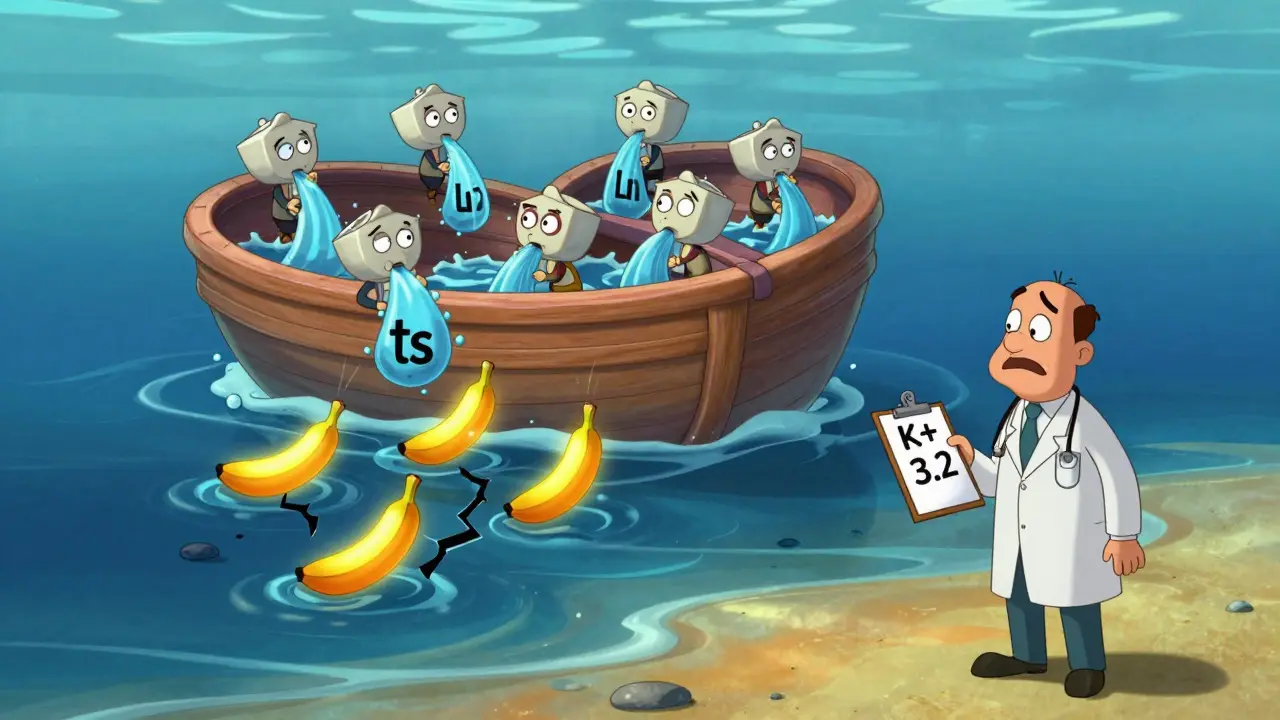

When someone has heart failure, fluid builds up in the body - lungs, legs, abdomen. That’s why doctors reach for diuretics, often called water pills. Loop diuretics like furosemide, bumetanide, and torsemide are the go-to. They work fast, pulling out excess fluid and easing shortness of breath. But there’s a hidden cost: hypokalemia. That’s when blood potassium drops below 3.5 mmol/L. It’s not rare. About 1 in 4 heart failure patients on loop diuretics end up with low potassium. And it’s not just a lab number - it’s a ticking time bomb for dangerous heart rhythms.

Why Low Potassium Is Dangerous in Heart Failure

Potassium isn’t just for bananas. It’s what keeps your heart beating regularly. When levels dip below 3.5 mmol/L, the electrical signals in the heart get messy. In someone with damaged heart muscle - common in heart failure - this can trigger ventricular arrhythmias. Studies show that potassium levels under 3.5 mmol/L double the risk of death in these patients. The danger isn’t just from the low number itself. It’s the combo: diuretics stripping away potassium, plus other meds like ACE inhibitors or SGLT2 inhibitors that can shift electrolytes around. Even mild drops, like 3.2 mmol/L, can make arrhythmias more likely.

How Diuretics Cause Potassium Loss

Loop diuretics block a salt pump in the kidney called the Na+-K+-2Cl- cotransporter. That sounds technical, but here’s what it means in real terms: more sodium gets pushed into the urine. To balance that, the kidney dumps even more potassium out. The higher the diuretic dose, the worse it gets. And here’s the twist: giving one big morning dose of furosemide doesn’t work as well as splitting it. Why? Because the kidney starts holding onto salt again after the first dose wears off. That’s called “within-dose tolerance.” Giving furosemide twice a day - say, 20 mg at 8 a.m. and 20 mg at 4 p.m. - keeps the diuretic effect steadier. That also means less wild swings in potassium levels.

What the Guidelines Say About Monitoring

The 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guidelines are clear: check potassium before starting diuretics, then again within a week, then monthly if stable. But in real life, patients get discharged after a few days in the hospital and don’t come back for weeks. That’s a problem. If potassium drops to 3.0 mmol/L by day 5, you’ve already increased their risk of sudden cardiac arrest. The rule of thumb: monitor every 1-3 days during acute decompensation or when doses change. If they’re on high doses or have kidney disease, check even more often. Don’t wait for symptoms like weakness or palpitations - by then, it’s too late.

How to Fix It: Potassium Supplementation

If potassium is 3.0-3.5 mmol/L, start with oral potassium chloride. Dose: 20-40 mmol per day. That’s about two to four tablets, depending on the strength. Split the dose - one in the morning, one in the evening - to avoid stomach upset. For levels under 3.0 mmol/L, you need IV potassium. But don’t rush. Give no more than 10 mmol per hour, and always monitor the ECG. Rapid IV potassium can stop the heart. And never give IV potassium without a line going into a large vein. Peripheral lines are a no-go.

The Game-Changer: Potassium-Sparing Medications

Instead of just replacing potassium, why not stop the leak? That’s where mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) come in. Spironolactone and eplerenone block aldosterone - the hormone that tells the kidney to dump potassium. The RALES trial in the 90s showed spironolactone cut death risk by 30% in severe heart failure. Today, we know why: it stabilizes potassium and protects the heart muscle. Start low: spironolactone 12.5 mg daily or eplerenone 25 mg daily. Check potassium in 5-7 days. If it’s under 5.5 mmol/L and kidney function is okay, you can increase it. These drugs aren’t just for potassium - they’re life-saving.

SGLT2 Inhibitors: The Quiet Hero

Empagliflozin and dapagliflozin were once just diabetes drugs. Now they’re standard in heart failure - even if the patient isn’t diabetic. Why? They reduce fluid overload without touching potassium. In fact, they slightly raise it. Clinical trials show SGLT2 inhibitors cut diuretic needs by 20-30%. Less diuretic = less potassium loss. That’s huge. They also improve outcomes independent of glucose control. Start at 10 mg daily. No dose adjustment needed for kidney disease. And they’re safe even when potassium is 4.0 mmol/L. This isn’t an add-on - it’s a cornerstone.

What About Diet and Salt?

Patients are told to cut salt. But too little salt can backfire. Restricting sodium to under 2 grams a day raises aldosterone, which makes the kidneys dump even more potassium. The sweet spot? 2-3 grams of sodium daily (80-120 mmol). That’s not zero - it’s enough to keep the body from overcompensating. Encourage foods with natural potassium: avocado, spinach, beans, potatoes. But don’t rely on diet alone. You can’t eat your way out of a 3.1 mmol/L potassium level.

When to Add Another Diuretic

Some patients need more than a loop diuretic. If they’re still swollen despite high doses, adding a thiazide like metolazone (2.5-5 mg daily) can help. It works downstream, where loop diuretics lose their punch. But here’s the catch: thiazides also cause potassium loss. So if you add metolazone, you must also increase potassium support or add an MRA. This combo is powerful but risky. Use it only in resistant cases, under close watch.

Special Cases: HFpEF vs. HFrEF

Not all heart failure is the same. Patients with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) don’t respond to diuretics like those with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Aggressive diuresis in HFpEF can hurt kidney function without helping fluid removal. So in HFpEF, aim for gentle, steady fluid removal. Don’t chase weight loss. Target a 0.5-1 kg/day drop. Pushing harder doesn’t help - it just makes potassium drop faster. HFrEF patients can handle more aggressive diuresis, but still need tight potassium control.

What to Avoid

- Don’t use potassium-depleting laxatives or enemas. They’re common in elderly patients and can crash potassium levels overnight.

- Avoid NSAIDs like ibuprofen. They reduce kidney blood flow and make diuretics less effective - leading to higher doses and more potassium loss.

- Don’t assume normal potassium means safe. A level of 4.0 mmol/L might look fine, but if it dropped from 5.0 last week, the heart is still at risk.

Putting It All Together: A Simple Plan

Here’s how to manage this in real life:

- Start with a loop diuretic - furosemide 40 mg twice daily, not once.

- Add an MRA: spironolactone 12.5 mg daily or eplerenone 25 mg daily.

- Start an SGLT2 inhibitor: dapagliflozin or empagliflozin 10 mg daily.

- Check potassium at day 5, then weekly until stable.

- If potassium is 3.2 mmol/L, add oral KCl 20 mmol/day.

- If it drops below 3.0 mmol/L, pause diuretics, give IV potassium, and reassess.

- Keep sodium intake at 2-3 g/day. Don’t go lower.

- Never use NSAIDs. Avoid laxatives.

This approach cuts hypokalemia risk by over 50% in studies. It’s not magic - it’s logic. You’re not just treating fluid. You’re protecting the heart’s rhythm.

Can I just give potassium pills without changing the diuretic?

No. Giving potassium alone is like plugging a leak while the faucet is still running. You’ll keep chasing low numbers. The real fix is reducing potassium loss at the source - by adding a potassium-sparing drug like spironolactone or switching to a lower diuretic dose with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Potassium pills help, but they’re not the solution.

Is hypokalemia more dangerous in elderly patients?

Yes. Older patients often have reduced kidney function, take more medications, and have more heart disease. Their bodies handle potassium shifts less well. A potassium level of 3.3 mmol/L might be fine in a young person, but in someone over 75 with prior heart attack, it’s a red flag. Monitor more closely. Avoid high-dose diuretics. Prefer lower doses with MRAs and SGLT2 inhibitors.

Do I need to stop diuretics if potassium is low?

Not always. If potassium is 3.2 mmol/L and the patient is stable, continue the diuretic but add an MRA and oral potassium. Only stop diuretics if potassium is under 3.0 mmol/L, the patient is symptomatic (weakness, palpitations), or they’re in acute decompensation. The goal is to keep them dry without letting potassium crash.

Can SGLT2 inhibitors replace diuretics entirely?

No. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce fluid overload, but they’re not strong enough to replace loop diuretics in moderate-to-severe heart failure. They’re best used together. Think of them as a helper - they cut diuretic needs by 20-30%, which reduces potassium loss and makes the whole treatment safer. But they won’t clear severe lung congestion on their own.

What if potassium keeps dropping despite all interventions?

Look for hidden causes: laxative abuse, vomiting, diarrhea, or poor nutrition. Check for drug interactions - especially with corticosteroids or amphotericin B. If all else fails, consider switching from furosemide to torsemide. Torsemide has better bioavailability and a longer half-life, which can lead to more stable potassium levels. Also, consider a low-dose thiazide only if the patient has severe fluid overload and you’ve optimized everything else.