When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, the hope is that cheap generics will flood the market, driving prices down and saving patients and insurers billions. But in many cases, something else happens: the same company that made the original drug launches its own authorized generic - identical in every way - just as the first independent generic enters. And that single move can crush the entire competitive process.

What Exactly Is an Authorized Generic?

An authorized generic is not a new drug. It’s the exact same pill, capsule, or injection as the branded version, just repackaged with a generic label and sold under a different name. The manufacturer? Usually the same company that holds the patent. They don’t need new FDA approval because they’re using their own original drug application. All they do is slap a new label on it and ship it out.

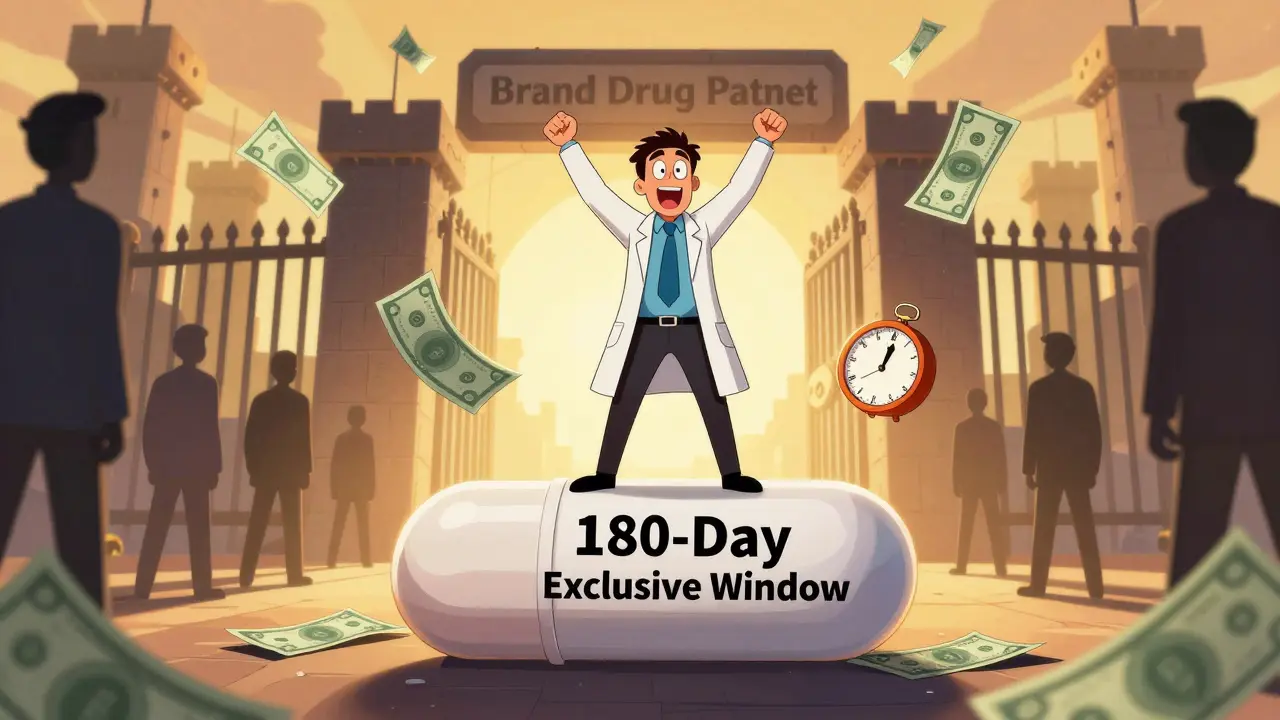

This isn’t a loophole. It’s a legal right under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. The law was meant to speed up generic entry by giving the first generic company to challenge a patent a 180-day exclusivity period - a reward for taking the legal risk. But the law never said the brand company couldn’t jump in with its own version. And that’s where things get messy.

The 180-Day Exclusivity Trap

Imagine you’re a generic drugmaker. You spend millions suing a brand company over a patent you believe is invalid. You win. Now you get the exclusive right to sell the generic for six months. That’s your payoff. You launch. Prices should plummet. Patients benefit.

But then, two weeks later, the brand company drops its own authorized generic on the market. Same formula. Same manufacturer. Same factory. Just a different label. And it’s priced not at generic levels - but somewhere between the brand price and the real generic.

What happens? The first generic’s sales collapse. The FTC found that when an authorized generic enters, the first-filer generic loses 40-52% of its revenue during that 180-day window. In markets without authorized generics, that first generic captures 80-90% of the generic market. With one in play? It’s lucky to get 30%.

This isn’t competition. It’s sabotage dressed up as choice.

How Authorized Generics Kill the Incentive to Challenge Patents

Why would any generic company risk a lawsuit if they know the brand can just flood the market with its own version and steal their profits?

The numbers tell the story. For drugs with annual sales between $12 million and $27 million - small by industry standards but still meaningful - the threat of an authorized generic can make a patent challenge financially unviable. The Congressional Research Service found that this fear alone reduces the number of patent challenges for these drugs. And these aren’t rare cases. Between 2005 and 2010, authorized generics appeared in 47% of all markets where a first-filer had exclusivity. That’s nearly half the time.

It’s not just about lost revenue. It’s about deterrence. Generic companies now do the math before they sue. If the brand has a history of launching authorized generics, they walk away. That means fewer challenges. Fewer challenges mean fewer generics. Fewer generics mean higher prices - for years.

Reverse Payments and Secret Deals

The worst part? It’s not always just a business decision. Sometimes, it’s a bribe.

From 2004 to 2010, about 25% of patent litigation settlements between brand and generic companies included an explicit promise: "We won’t launch an authorized generic if you delay your generic launch." These are called "reverse payments" - the brand pays the generic to stay out of the market. And in many cases, the payment isn’t cash. It’s the promise not to launch an authorized generic.

These deals delayed generic entry by an average of 38 months. That’s over three years of monopoly pricing. And it happened on drugs worth more than $23 billion in annual sales.

The FTC called these arrangements "the most egregious form of anti-competitive behavior in the pharmaceutical sector." Courts have ruled that reverse payments can violate antitrust laws - but authorized generics slipped through the cracks. Until now.

Why the FTC Is Fighting Back

The Federal Trade Commission has been warning about this for over a decade. Their 2011 report showed authorized generics weren’t just hurting generic companies - they were breaking the entire system Congress designed to lower drug prices.

In 2022, the FTC made it clear: they’re targeting these deals. Director Holly Vedova said the agency will challenge "any arrangement that uses authorized generics to circumvent the competitive structure Congress established in Hatch-Waxman." Since 2020, the FTC has opened 17 investigations into suspected anti-competitive behavior involving authorized generics. They’re not just watching - they’re preparing lawsuits.

And they’re not alone. Senators Amy Klobuchar and Chuck Grassley reintroduced the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act in March 2023. This bill would ban agreements that delay authorized generic entry. If it passes, secret deals like the ones from 2004-2010 could become illegal.

Who Benefits? Who Loses?

Branded drug companies say authorized generics help consumers by adding competition. They point to a 2022 Health Affairs study claiming pharmacy prices were 13-18% lower when an authorized generic was available. But here’s the catch: that price drop is still far above what true generic competition delivers. The authorized generic doesn’t drop to $5 a pill - it drops to $15 while the real generic sits at $8. That’s not competition. That’s price suppression.

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) often support authorized generics because they give them another pricing tier to negotiate with. But patients? They don’t care about PBM rebates. They care about what’s on their receipt at the pharmacy counter.

Independent generic manufacturers? They’re getting crushed. Teva Pharmaceutical reported a $275 million revenue loss in 2018 - directly tied to authorized generics. Smaller generic companies? Many have gone out of business after being undercut by their own former competitors.

Patients lose most of all. When fewer generic companies challenge patents, fewer drugs get cheaper. When authorized generics dominate the early market, true generic entry is delayed. And when generic entry is delayed, prices stay high.

Is This Practice Still Common?

It’s declining - but not because companies are doing the right thing.

A 2023 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that authorized generics launched in only 28% of eligible markets in 2022, down from 42% in 2010. Why? Because the legal risk has gone up. The FTC is watching. Courts are more skeptical. Companies are afraid of being sued.

But here’s the twist: companies haven’t stopped using authorized generics. They’ve just gotten smarter. Instead of announcing a deal upfront, they now wait. They let the first generic enter. They monitor sales. And if the generic is doing well, they launch their own version - claiming it’s "just a business decision." The timing is always convenient. Usually, it’s within a week of a court ruling against the brand’s patent.

And in 92% of recent patent settlements, legal teams now include clauses about authorized generic timing. These aren’t accidental. They’re calculated.

The Bottom Line

Authorized generics aren’t helping patients. They’re protecting profits.

The Hatch-Waxman Act was supposed to make drugs affordable. Instead, it gave brand companies a legal tool to outmaneuver the very system meant to break their monopoly. Authorized generics don’t create competition - they mimic it. They create the illusion of choice while quietly preserving high prices.

Until Congress closes this loophole - or the FTC successfully shuts down these deals - patients will keep paying more than they should. And the real winners? The companies that know how to play the game.

Are authorized generics the same as regular generics?

Yes, in terms of ingredients, dosage, and effectiveness. An authorized generic is chemically identical to the brand-name drug. The only differences are the label, packaging, and manufacturer. The brand company produces it themselves - often in the same factory - and sells it under a generic name. Regular generics are made by independent companies that reverse-engineered the drug and got FDA approval through an ANDA process.

Why do brand companies launch authorized generics?

To protect their profits. When a patent expires, the first generic company gets a 180-day exclusivity period and can charge much less than the brand. But if the brand launches its own authorized generic at the same time, it captures a big chunk of that market - often 25-35% - at a price higher than the real generic. This reduces the first generic’s revenue, discourages future challenges, and keeps overall prices higher than they’d be with true competition.

Is it legal for a brand company to launch an authorized generic during the first generic’s exclusivity period?

Yes, it’s currently legal under the Hatch-Waxman Act. The FDA allows it because no new approval is needed - it’s the same drug. But while it’s legal, it’s increasingly controversial. The FTC argues it undermines the purpose of the exclusivity period, and courts are starting to treat agreements to delay authorized generics as potential antitrust violations.

Do authorized generics lower drug prices for patients?

Sometimes, but not meaningfully. Authorized generics are priced between the brand name and true generics - often 15-20% below the brand but 25-30% above the real generic. So while patients might pay a little less than the brand price, they’re still paying far more than they would if a true generic had full market access. The real price drop comes only when multiple independent generics enter - something authorized generics actively prevent.

What’s being done to stop this practice?

The FTC is actively investigating and suing companies that use authorized generics to delay competition. In 2022, they declared such arrangements a priority enforcement area. Congress is also considering the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, which would ban agreements that delay authorized generic entry. Some companies are also backing off due to legal risk - but the practice hasn’t ended.

How do authorized generics affect generic drug manufacturers?

They hurt them badly. When an authorized generic enters, the first-filer generic’s revenue drops by 40-52% during its 180-day exclusivity window. In the following 30 months, their revenue remains 53-62% lower than it would be without an authorized generic. Many smaller generic companies have gone out of business after losing key products to this tactic. It’s a direct attack on the incentive to challenge patents - the very foundation of generic drug competition.

15 Comments

Barry Sanders

Authorized generics? More like authorized exploitation. Brand companies are laughing all the way to the bank while patients get screwed. This isn't capitalism-it's corporate theft with a FDA stamp.

Chris Ashley

Bro, I just paid $45 for a generic that’s literally the same pill my dad gets for $8. This system is broken. Someone’s making bank and it ain’t us.

kshitij pandey

Hey friends, I come from India where generics save lives every day. This practice? It breaks my heart. People in the US deserve affordable medicine too. Let’s fix this together. 💪

Brittany C

The Hatch-Waxman Act’s original intent was clearly subverted by strategic market manipulation. The authorized generic mechanism functions as a regulatory arbitrage tool that distorts the price elasticity curve in the post-exclusivity window.

Sean Evans

These pharma CEOs are criminals. 😡 They literally use the law to cheat. And you know what? I'm not just mad-I'm filing a complaint with the FTC right now. Someone needs to go to jail for this. #JusticeForPatients

Anjan Patel

Ohhh, so this is how the big boys play? They let the little guy fight the patent battle, then swoop in with their own version like a vulture? Disgusting. And the worst part? They call it "competition." Pathetic.

Scarlett Walker

I used to think generics were the hero here... but now I see they’re the ones getting stabbed in the back. It’s wild how the system was built to help people, but got hijacked by greed. We need to fix this.

Hrudananda Rath

It is an incontrovertible fact that the proliferation of authorized generics constitutes a pernicious distortion of the market equilibrium, thereby undermining the very foundations of antitrust jurisprudence and the public interest imperative for pharmaceutical affordability.

Brian Bell

Yeah, I saw this happen with my insulin. Brand was $300. First generic was $120. Then the brand dropped their "generic" at $180. Sales of the real generic tanked. I cried in the pharmacy. 😔

Nathan Hsu

Let me be perfectly clear: this is not merely a business strategy-it is a systemic abuse of regulatory frameworks, and it must be addressed with urgency, precision, and unwavering resolve!

Ashley Durance

People think this is about drugs, but it's about power. The brand companies control the FDA filings, the manufacturing, the distribution. They own the game. The rest of us are just playing checkers.

Scott Saleska

It's funny how everyone says "competition is good" until the competition actually threatens their profits. Then suddenly, it's "market manipulation." Pick a side, folks.

Ryan Anderson

FTC needs to move faster. This isn’t just unethical-it’s illegal under antitrust law. I’ve seen the data. The numbers don’t lie. Someone needs to sue these companies into oblivion. 🙏

Eleanora Keene

So… if the brand company makes the exact same pill, why can’t we just buy the brand version and call it a day? Why does the label even matter? Just wondering…

Joe Goodrow

Why are we letting foreign generic makers ruin American pharma? This is why we need tariffs. This is why we need America First. Authorized generics? That’s just the FDA helping the enemy.